|

Hill 501

Forward

Ernie Pyle once said that an individual G I' s knowledge of the war

covered no more ground than the few yards on either side of him. Years

after our combat days in the 89th Division, several of us wondered

whether we could pool our recollections to build a more complete

picture of some memorable event we had all experienced.

This narrative is an attempt to do just that. It draws on

letters, newspaper clippings, e-mails and U.S. Army citations.

Quotations in it aren't always exact. Fragments of conversation are

often pasted together. The intent is to create as accurate a picture as possible of a March

20, 1945 assault on a hill in southwestern Germany.

Narrative

We called it Hill 501. It was actually Limbacher-Hohe, one of those

lovely green highlands in the Rhineland-Palatinate area of Germany,

south of the Moselle River. On March 20, 1945, as the American armies

closed on the Rhine, our battery of 105mm howitzers started to follow

Company F of the 353rd Infantry up that hill.

Darrel Carnell was driving Captain Lewis Van Loten's Jeep, the lead

vehicle in our B-340 convoy. He remembers that they had a German

prisoner in the back seat, a young enlisted man who was certainly no

veteran Wehrmacht soldier. Where he had come from or how they had

captured him, Carnell has long since forgotten.

"The terrain as we approached the hill," Carnell says, "became

gradually more rugged - a sharp, wooded embankment to our left and

a shallow ravine leading steeply up to another wooded area on our

right. We began to hear the crackle of small arms coming from the

wooded area on the right, but we weren't sure at first whether it was

our guys or the Krauts. Then the gunfire began popping pretty good,

so we jumped out of the Jeep and put it between us and the noise.

Our prisoner didn't understand English, but he understood danger and

he hopped right out with us."

Near the summit, the infantry had run into a lot of trouble. Unknown

to them, Hill 501 was a fortified anti-aircraft position, with a

concrete pillbox, some 88mm and 20mm guns, machine guns and a lot of

other small arms, including sniper rifles with 10 power scopes.

John Hebert, 1st Scout and a sniper for his infantry platoon, was

the first to see the enemy.

"I signaled back that the enemy was in sight," Hebert remembers,

"and within a few seconds our platoon leader, Lt. Earl Oot,

and our platoon sergeant, Sgt. M. J. Markley, were on their way up,

but before they arrived, all hell broke loose. The enemy opened

up on us with everything they had and at that time I didn't think many

of us would survive. Under the direction of Oot and Markley, however,

we began to lay down some very accurate fire. As I recall,

our artillery support was delayed, but once they did get set up,

their fire was very much on target."

Ed Quick was a cannoneer in #2 gun section of B battery and he

remembers why the artillery fire was so slow in responding. "When the

fire mission was called," he says, "we pulled over into that shallow

ravine Carnell mentions and attempted to set up our howitzer, but had

no success at all. The ground was so uneven that we couldn't get the

gun level enough to fire. Only #1 gun was able to find a spot flat

enough. Once the Battery Executive Officer was able to lay at least

that one gun, it began to fire, and in short order went through

all of its ammunition. We had to carry ammo from our section on the

double up to #1 Gun's crew to replenish their supply. We heard that

their fire was very effective."

Since the battery had only one gun firing, Regimental Fire Direction must

have called on other outfits to help out. Lt. Rowland Shriver, Battery C,

340th, earned a Bronze Star. His citation reads, in part:

"On March 20, near Limbacher Hohe, when his forward observers were immobilized

by enemy fire, Lt. Shriver voluntarily moved forward under heavy enemy

and small arms fire, to adjust friendly artillery fire that resulted in

neutralizing the enemy's 88mm and 20mm guns. This action enabled the

infantry to advance and take its objective."

A radioman from Headquarters Battery of the 340th also earned a Bronze

Star that day. According to the 89th History book, Pfc. Ernest

Storzer carried his radio up the hill in full view of the enemy, and

while under intense fire, directed artillery into the German position.

In taking 501, our infantry suffered a number of casualties and John

Hebert remembers the violence. "We tried to assault the enemy's

position but their fire was so heavy we had to hit the ground and look

for cover. Kenneth Haines, Rudy Triviso, and several others were

caught with me in the open with no means of concealment. Anti-aircraft

shells were bursting overhead and a German machine gun started to fire

at us. Haines opened up with his M-1 rifle and fired a full clip of

tracers at it. I knew that if that machine gun wasn't put out of action,

it would probably kill five or six of us. Well, Ken knocked that

machine gun out alright but just as he fired his last round, a German

sniper shot him right between the eyes, killing him instantly.

"The sniper then zeroed in on me, but his shot missed my head and

took a piece out of my combat boot heel. I killed him with my sniper's

rifle, an 03-A4 with a 2 ½ power scope. Then I shot another German

before making a dash to the left to a better position in some bushes.

From there, I saw my buddy, Fred Kirk, the oldest man in our company,

get hit. His condition looked very bad and the medic was pinned down by

machine gun fire. In order to get to him, I had to knock out that

machine gun first, and after I did that, I crawled out and dragged

Fred back to where the medic could treat him. His wounds were so bad,

though, that he died soon afterward.

"A short distance away, on my left, Earl Nordin, the youngest man in

the company, was hit and killed. About that time, I noticed some German

soldiers advancing toward our position, so I circled around behind them

and was able to capture all six of them. I don't know how many

casualties we had that day, but it could have been much worse when you

consider all that we ran into."

For his gallantry in action, John Hebert was awarded the Silver

Star. He thought at the time that others in his platoon also

deserved decorations, especially Lt. Oot and Sgt. Markley, who showed

outstanding bravery. Markley did receive a Bronze Star for "leading

his platoon over exposed ground under small arms fire to capture

47 Germans," and Lt. Oot was also awarded a Bronze Star.

Hebert's Silver Star citation reads in part:

"On his own initiative, Pfc. Hebert daringly advanced to a vantage point

and killed two snipers. Then, seeing a wounded comrade, he crossed through

heavy machine gun fire to him, administered first aid under fire and then moved

the wounded man 75 yards to a place of safety. Continuing in the

attack, he captured six enemy riflemen and thereby enabled his platoon

to take its objective."

In September, 1999, The Globe Gazette, a local paper in Fred Kirk's

home town of Fertile, Iowa, carried the story of a memorial service

held in a Luxembourg cemetery for Kirk and forty five other 89th

Division soldiers. Their graves are in a small grass covered cemetery, the

same cemetery in which General George Patton is buried. During the

ceremony, the names of the forty six men were read and a wreath was

placed on Kirk's grave. The newspaper account mentions that John

Hebert wrote to Kirk's family some years ago and told them the

circumstances surrounding his death. Fred Kirk was 39 years old

when he died.

After the battle for Limbacher Hohe was over, we hooked up our

howitzers, climbed onto the gun trucks and once again followed the

old man's Jeep up the hill. This time, we made it to the top

without incident. The first thing Carnell remembers seeing there was

an abandoned German motorcycle.

"A burned out troop carrier was a little way beyond that motorcycle,"

he recalls, "I think it was some sort of half track vehicle and

looked as if it would carry about twenty men. There was a 20mm gun

emplacement on the hill and a few of the guys were foolishly trying to

disarm some of its cartridges to make souvenirs. Lucky no one lost a

hand."

Quick also remembers the troop carrier.

"The corpse of a burned-to-a-crisp German soldier was leaning halfway out

of the driver's seat, his clothes burned off and his body split wide

open, the bright red flesh and white bones looking like a rib roast in a

butcher shop. A shiny gold wedding ring was on one of his blackened fingers."

One of our men had a thieving eye, and even as we yelled at him to stop

it, he tried to remove the ring. When it wouldn't come off, he took

out his trench knife and cut off the dead man's finger. It was the

last time this particular man stole jewelry from a corpse. Several

weeks later, as he attempted to take a wristwatch from a dead American

tanker, Carnell had had enough. He leveled his carbine at the guy

and told him to knock it off. The man hesitated and then backed away,

and never again tried to scavenge personal belongings from the

dead, at least not while anybody was around.

Both Carnell and Quick saw the bodies of the Americans killed that

day lying on the wet grass - Kenneth Haines, Fred Kirk and Earl

Nordin - three of the four F Company men lost in combat . They had

been moved to the edge of the road for access by Graves Registration,

and Carnell recalls his thoughts as he looked at them lying there. "They

were dressed just like us and THEY LOOKED EXACTLY LIKE ME. Same shirt,

same pants, same boots, same everything that I was wearing. A

somber sight."

One of the men lay bareheaded on the grass. Quick had a fleeting

crazy notion that someone ought to put something under the man's head

because he was getting his hair all wet.

The war had become much more real to us. The three GI's there on

the grass were the first Americans killed in action that we had

seen, and we regarded them gravely. These young guys were

members of the same club we all belonged to. They were the guys you

called "Mac" or "Buddy" even though you didn't know them. Nobody said

much for a while.

There were lighter moments on Limbacher Hohe. Someone found an

old wind-up 78 rpm phonograph and a stack of German records. As we

ate our C-rations that noon, we listened to a singer who sounded like

Marlene Dietrich wailing out the scratchy blues. Carnell filled the

tank of the motorcycle and he and a buddy roared away down the road.

"I must have roared for about a couple of minutes before the bike quit

on me," he remembers, "and I couldn't restart it. That's when I

learned about two cycle engines which need to have oil mixed with the

gasoline!"

A concrete fortification sat on the brow of Hill 501, its gun slots

looking out over the valley below. It was mostly underground and had

an unpleasant dank smell inside. We thought maybe the Germans had used

part of it as their latrine. A story circulated that a number of

Lugers and P-38's had been left in the pill box by the Germans, but a

Master Sergeant from Headquarters, the machine gunner in the Battalion commander's

Jeep, had cleaned them all out before we arrived. A beautiful black

helmet with a red and gold shield painted on its side lay just outside

the entrance, but since it looked as if it might be booby trapped, it

was left alone. Carnell found a nice Luger beneath the body of a dead

Wehrmacht soldier, and others of us picked up belt buckles, daggers and

other paraphernalia left behind by the retreating Germans.

In the relatively brief firefight on Limbacher Hohe, the Germans lost a

dozen men and F Company three. Over fifty Germans were captured, and

the rest of the Wehrmacht unit defending the hill fled. It was a day of

courage and "above and beyond the call of duty" action, and on that day,

one Silver Star and four Bronze Stars were earned.

Note: Limbacher Hohe is located near the town of Limbach. The

word Hohemeans "Height" or "Hill" in German. A loose translation might

therefore be "Limbach Hill."

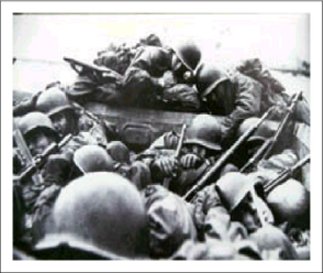

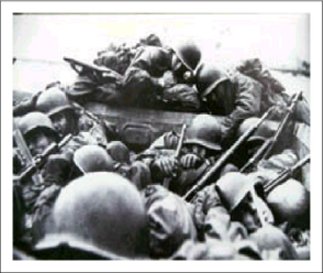

John Hebert's and other members of F Company,

353rd Infantry, are shown crossing the Rhine River in DUKW #24.

Hebert is on the right in the photo, facing directly into the camera,

with his sniper's rifle leaning against the side of the vessel.

He says the picture was taken by Sgt. Herz of the 166th Signal

Photo Co. Also in this photo (which faces the bow of the boat)

is Sgt. Rulo of F Company.

|

|